On Carlos’ clavier

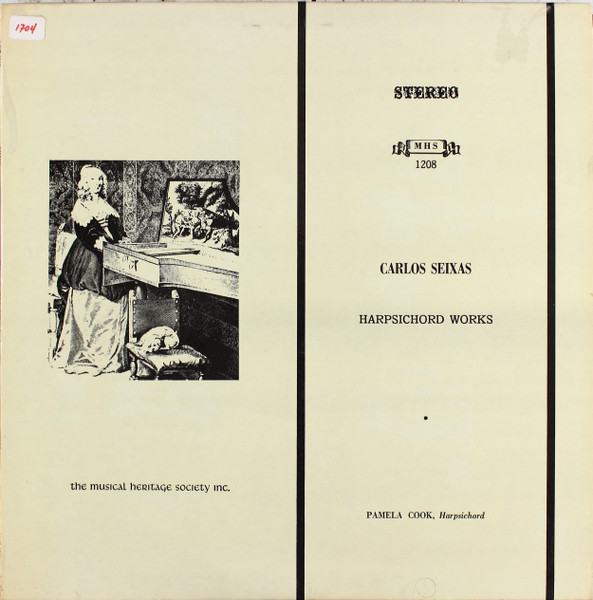

I recently came across this album of Harpsichord Works, written in the early 18th century by the Portuguese composer Carlos de Seixas and recorded by American musician Pamela Cook in the late 20th, by accident; I was searching for out-of-print recordings of the great master Scott Ross, and found this jaundiced LP. Unfamiliar with Sexias, I was surprised to find him praised by Scarlatti as one of the best musicians he had ever heard. And then I played the album.

Great art is not perfect, but perfects. I confess that the word “virtuoso” conjures in me a definite disdain, and I avow that showy productions of technical execution turn over my eyes. But these sonatas and toccatas are different: from the thundering cavalcade of “Sonata in A minor” to the languid arabesque of her sister “in E minor”, Seixas’—as well as Cook’s—mastery of the keys is evident; yet even from across the centuries it is his beating heart, not her dancing fingers, that strike me. These Works invert the stereotype of baroque music as festooned with gaudy ornament: here, hearers are stripped of their idle embellishments. No, this is not antiquarian “easy listening”, but the attention demanded is recompensed and more.

To be sure, I do not want to give an impression that the album is stuffy—in faith, it can be bracing. As Cook plays, we circumnavigate human affect: anon tender, anon ecstatic, here soaring, there searching; and it is the continuity of the clavecin that brings all to unity. A resounding peal in “Allegro in E Minor” alights into a gay ballet, and yet the whole hangs together. The balance struck on these pieces is fluid, like a fluttering hummingbird or a heaving barque: the composer and performer do not draw us a picture, but draw us through the picture. I sometimes felt rushed through a passage that I rather wished to have rested in a few moments more.

At other times I found myself baffled: Seixas’ “Sonata in G Minor” breaks out into a firefight, ringing out so many notes as almost to overshoot music and fall into din. Cook then follows with the “Sonata in E minor”, a cool and quiet abri. Lesser musicians could wear down the ears with such rolling and crashing energy, but the effects of this album are addictive rather than repellent: I often find myself turning its phrases over in my mind as I walk along the shore, especially these dramatic transitions. There is an affinity between the minor tonality and varied force of these tracks with the sea: those who have watched seabirds dive for fish or felt gales portending storm may understand the sober awe inspired when they consider the vast tracts of waves driven by the far-off moon and contested by the four winds.

I highly recommend this album, and will look for more of Sexias’ and Cook's work in the future. You can listen to the album entire on YouTube. For a more technical analysis of Seixas' œuvre, I recommend reading this dissertation by Dr. Brian J. Allison.